Dear subscribers and others,

I’ve been a bit word-tied lately. I mean certainly since about Christmas, and really before as well. A couple of times I’ve even tried to break out of it by writing a post here about being unable to write anything, and I couldn’t even make that make sense. So here is a slightly expanded version of a piece I published the other day on my work-&-writing website, katyevansbush.com.

I don’t often use this space to write about my own work, but after all, this website is about my own work. It’s about my work in editing, teaching, and writing — and amazingly, I have been writing again recently. It feels great, like not being a fraud any more.

Because really, who can be very happy when they’re not writing? It’s like the floodgates are closed, but with the flood kept in. It’s like I can hear everything that’s going on outside, but the window is shut. It’s like when you dream that you’re waking up but you can’t move. You’re speaking but no one can hear you.

Except that when you really aren’t writing, you can’t even find the words. It’s horrible. This condition comes to me from time to time, like insomnia, and one episode that made it really bad was the lockdown. It was too much like a vacuum. I tried all kinds of ruses, as we do: Write about what’s out the window. Write about what’s in the room. Write your most over-the-top, bored-shitless, frustrated, lonely and grief-stricken interior monologue. (You can bet that last one didn’t work! Although one of them I did manage to repurpose into a funny poem in two parts, the second of which is doggerel. Still unpublished, if you want it.)

But was this the kind of work I wanted to be writing? I had rooftops, and empty little town, and an allotment at my disposal. And virtually no form to speak of, just polite lightly accented free verse, droning down the page… It was boring me, even though I got reasonable mileage out of it. It felt dutiful to the point of fake. In fact, I was becoming a seething ball of rage: at the world, at the lockdown, at the government, at everyone who got to be locked down in their own neighbourhood with their own family & friends nearby — at everything. And I was just writing blah blah blah.

Also, of course, I have a book I’m meant to be writing, about the year I lost my home and months of sofa-surfing. I’ve worked on this in fits and starts, because it’s frankly quite difficult being in such a challenging situation and immersing yourself in yourself in another one that you already got out of. Or so you think. Every time you sit down and start writing, you realise you haven’t got out of it at all, because the past isn’t even past. It was easier writing about other people, so I’ve added a lot of researched material, and changed the focus a little. It’s the only way of making sense of things but it’s still too slow for a fast mind. (It’s so nearly done now! Very high on the to-do list.)

Well then, last August America was pulling out of Afghanistan and the enormity of it for the Afghans — and, frankly, the inability of almost Anyone I knew in America to be able to see it from that perspective — knocked me for six. I’ve hardly ever been so shocked or horrified by anything in my life. Poleaxed. That Saturday when we were all watching in horror as the Taliban advanced on Kabul, I found the yellow budgie who had been my faithful companion all through the lockdown and before it lying on the floor of his cage, dead. This was a tiny event, a tiny bombshell of an event, none the less so for its tinitude.

Later that day I went for a Long-Covid-related ECG, one of a string of such appointments, and felt, lying on the table, cared for. Later that day I wrote a poem. The first one in ages that had even begun to get at my real feelings — even if juxtaposing a parakeet with what was happening in Afghanistan felt gratuitous, emotionally it was all connected, just the immediacy of even a distant horror, because death itself and its sidekick, grief, are totalitarians and we’re all a tangle.

(And later it was taken by The Honest Ulsterman. A little encouragement never hurts.)

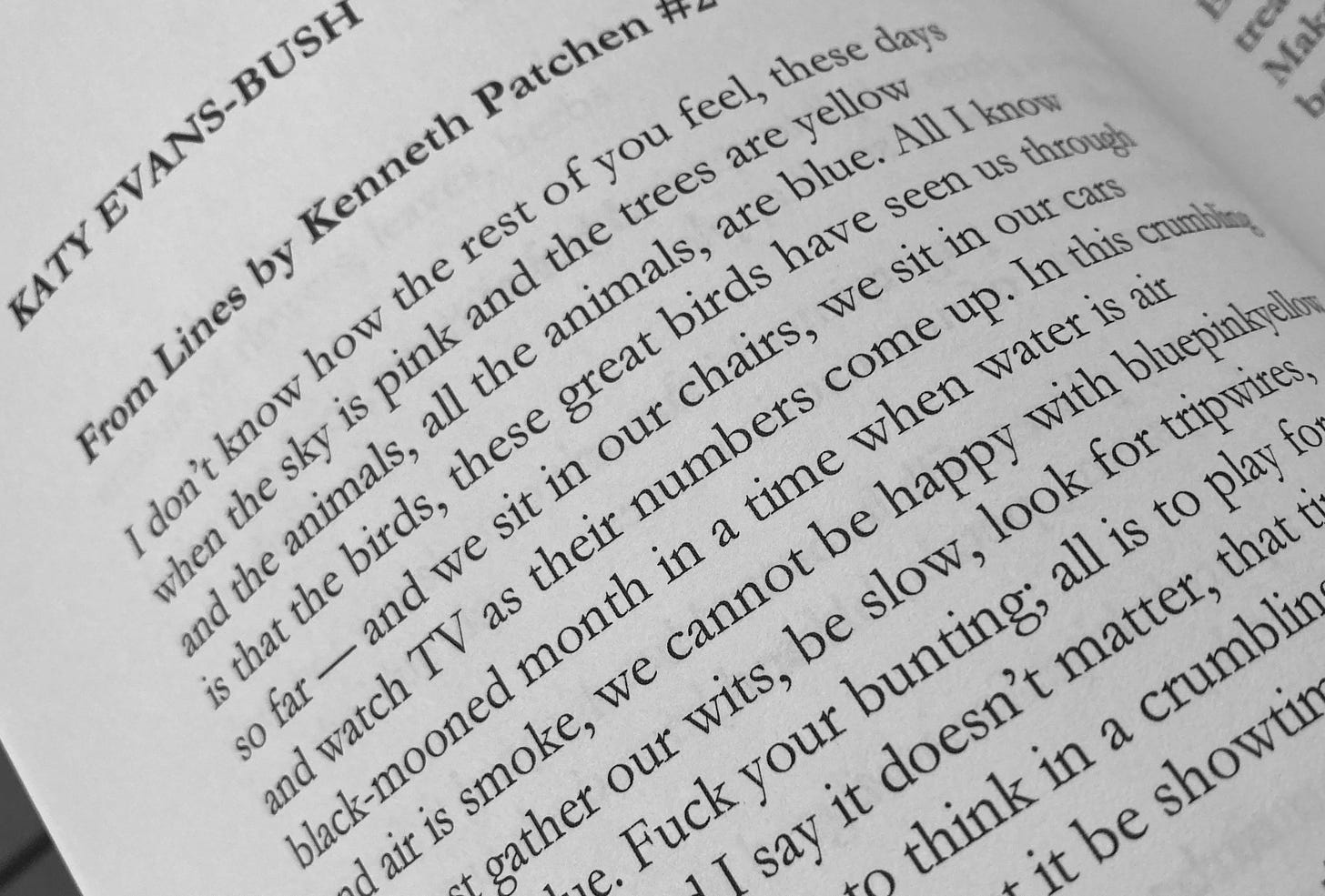

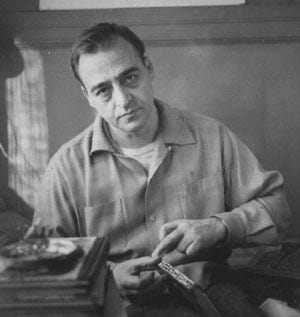

But it wasn’t enough to touch the sides. I thought of my poet friend Peter and his word tin: literally, his aunt’s old toffee tin full of cut-out words. Simple yet effective, for him at least, so I took out an old knackered book I’d had since I was 15, the Collected Poems of the proto-beat poet Kenneth Patchen, and started cutting. Patchen’s tone is high, and his poems are very uneven, but his phrases were much too good to take apart; who cares about colours when you can have stripes? I found myself cutting little confetti-strips with images or half-sentences on them. It didn’t take long to realise that I wasn’t going to be able to use any other words or phrases, that Patchen was speaking to me loudly in a voice I already knew well, that he was exhorting me to something, and that I was already in a conversation with him alone. He — my old poet daddy, master of discomfort & personal doubt, rager against the machine — told me he was going to free me from the confines of my lockdown displacement and that stifling politeness that (I think) must have come from the coruscating need for gratitude that homelessness (and that a new home, even one that’s far from home) foists on you. He promised me a return to myself, and isn’t each of us our own first home? I don’t have a toffee tin so I put them in a round, flat cardboard box that used to have a big delicious chocolate wafer from Warsaw in it.

When I was a teenager I loved this book to death. That it was in shreds testifies to his draw on my unformed mind, my need for external engagement, for the world, for politics, for great sweeps of Language with a capital L. And to my need to work out, once again, in my displaced state, who I am this time.

Because I’d been badly displaced the first time, too. From a much smaller city and a younger, but whole, life. And I guess what both of these events showed me is that you can’t just leave something; you have to be going to something as well. And if it’s too late, or you jumped only to avoid being pushed, you have to sit there and figure out where you are.

It’s not as if using cut-up phrases or words is a newfangled technique. Nothing is that kind of revolutionary or 'innovative’ any more. But it was the right one for the right moment. After all, writing is conversation. And when we really write we are inventing something totally new every time. Even so, it never occurred to me at the outset that I’d be putting myself back into that woods-surrounded bedroom in a little Victorian house with fishscale shingles on it, up a little hill in Collinsville, CT, where I once, long ago, also felt like a fish out of water… I came slowly, over several months, to realise this was what I was doing. I wrote a lot of poems in that other faraway room, too.

This is what happens when we write: we do something we don’t even know what it is. You go deep inside yourself, ideally while looking outward, and project yourself on an insoluble question — and maybe you come up with a partial answer. (It’s never the whole answer; how could it be? This is good news, by the way. It’s both why and how we keep going.) My friend Joe this morning posted a paragraph on Facebook about a stone near a bench on a boardwalk in Kent, and by the end of that paragraph he practically was that stone. You have to invest yourself, your real self, and what you’ll get back you never know in advance.

The morning after the cutting-up session I arranged four or five of Patchen’s phrases very quickly & matter-of-factly, like someone laying out tarot cards, one under another. A poem came bursting out round and through them. Three in a row. The next day four came in an hour. And so on. I would just keep going each time till the tap slowed to a trickle. It slowed down, of course, but seven months later, I have 41 poems, and over ten have been published. These phrases of Patchen’s have sparked a conversation with him — with myself — about politics, personal responsibility, death, bereavement, climate change, war, abortion rights, birds, flowers… They’ve got me writing in a looser & more open style, more like myself in fact. (I have a folder full of the poems I wrote when I was 16-17 and can attest to this. It’s not good poetry, but it does sound like me. And it sounds like me before I knew any different, which is the really encouraging thing.) This device, this letter, this poem-journal, this conversation with the past and with a surrogate Poetry Dad, has served me really well in a year of awful upheavals — just when we thought the world might be beginning to recover from its recent trauma.

You can see one of them on my website, and others in the autumn/winter 2021 issue of Raceme magazine, in Blackbox Manifold 27 (Winter 2021), four in the April 2022 issue of Shearsman magazine, and one forthcoming on the Poetry Wales blog, with a little interview about how it was written.