I bought myself an early birthday present yesterday, with money I don’t have — or more precisely won’t have in a month or two, and thus ‘shouldn’t spend’ — but the present itself is the proof that is in the eating, or looking. I needed it, and now I have it, and I’ll still have it in a month or two, and if I have to go homeless again it’ll go in my suitcase.

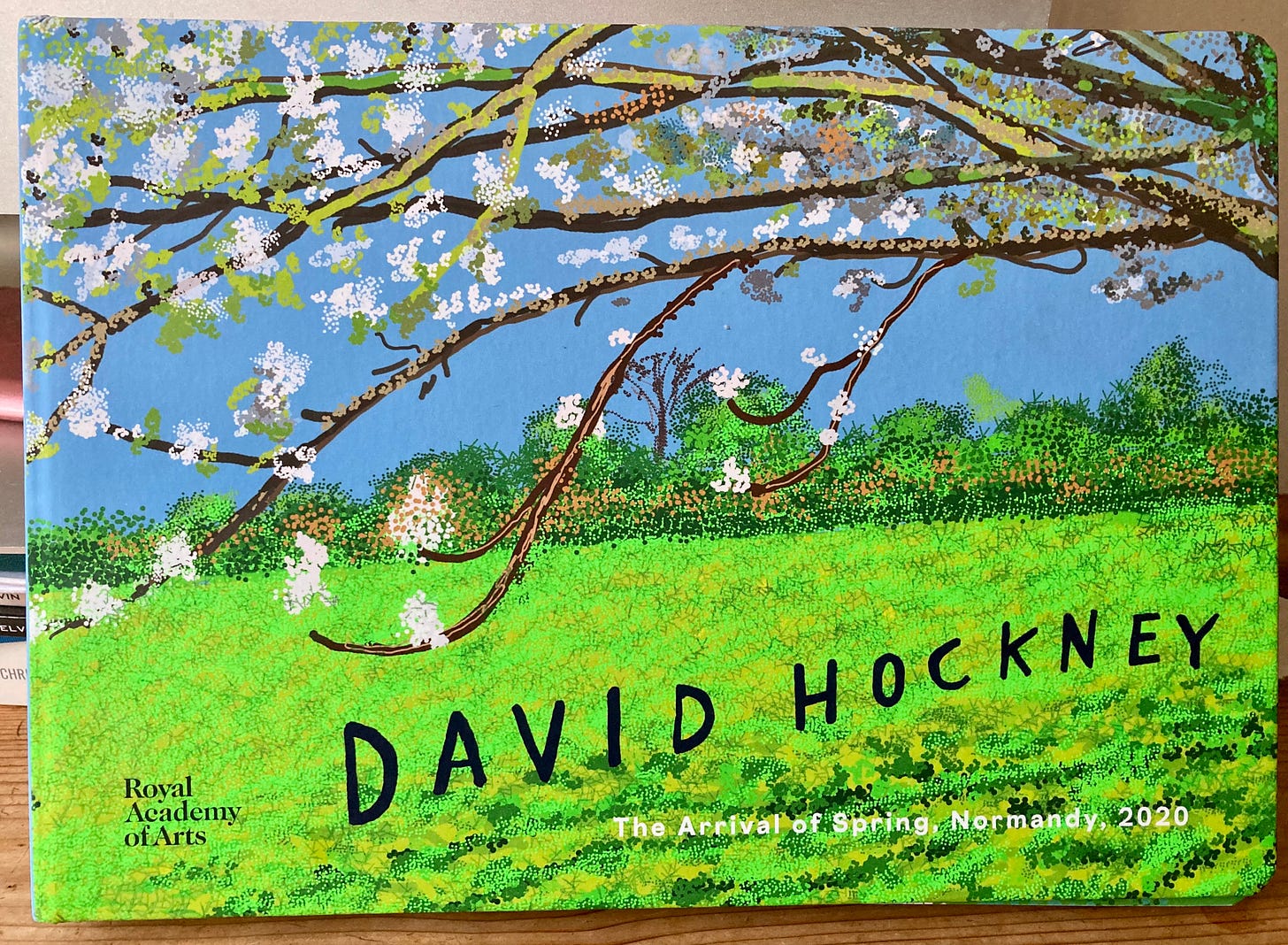

It’s very simple, what it is. It’s the exhibition book of David Hockney’s The Arrival of Spring, Normandy, 2020. A few friends of mine have been talking about the third anniversary of the start of the pandemic — specifically, of course, the first lockdown. I noted it on the 15th of March, because that was the day in 2020 when I walked into the market square about 200 yards from my flat, felt out of breath and then suddenly very tired, turned around, and by the time I got back was as if wrapped in a sheet of ice at the same time as burning up… and after that every single thing changed.

A friend of mine on Facebook, one of the Scottish poets, fell ill the same day as me, and we’ve been Long Covid buddies ever since. At the end of that day I went on Twitter and discovered that it, my ‘Covid birthday’, had also been International Long Covid Awareness Day. There was a hashtag, so I saw a lot of posts, some from poets — but one was from another guy, who I’d never seen before, who also got sick the same day as me. We now follow each other.

A few days ago I was looking for a nice picture to send with a birthday email to a family member. I thought of sending one of those nice Hockney spring pictures, and plumped in the end for the little clump of cheerful daffodils growing out of the grass. It’s a jolly, merry, happy-birthday sort of picture.

Looking at it, suddenly I could feel the hope of that spring. The extraordinary beauty of it, the warmth and sun — which for ages in that season I was missing, because I was inside, and not only do I have no garden; you can’t even see a single flower from my little picturesque medieval windows. The tops of trees in the municipal car park, over the rooftops across the little brick road — that’s it. So until the leaves came out, it still looked like February to me. I used to go sit in the unused car park across the road in the back, which is where my door is. An expanse of tarmac, but it was fresh air and sunshine. Especially after my friend Nessa gave me a folding lawn chair for my birthday. Once I started going around it seemed unbelievable that, from my perpetual winter, there was such a riot of blossom and flowers!

I don’t want to relive all that, but I’m also still grateful to my friend Joe, who helped me go to Morrison’s that first time, letting me lean on the trolley while he went up the aisles to get what I needed, and a little after that took me out to sit on a bench by the creek when I was getting better. The magic of it!

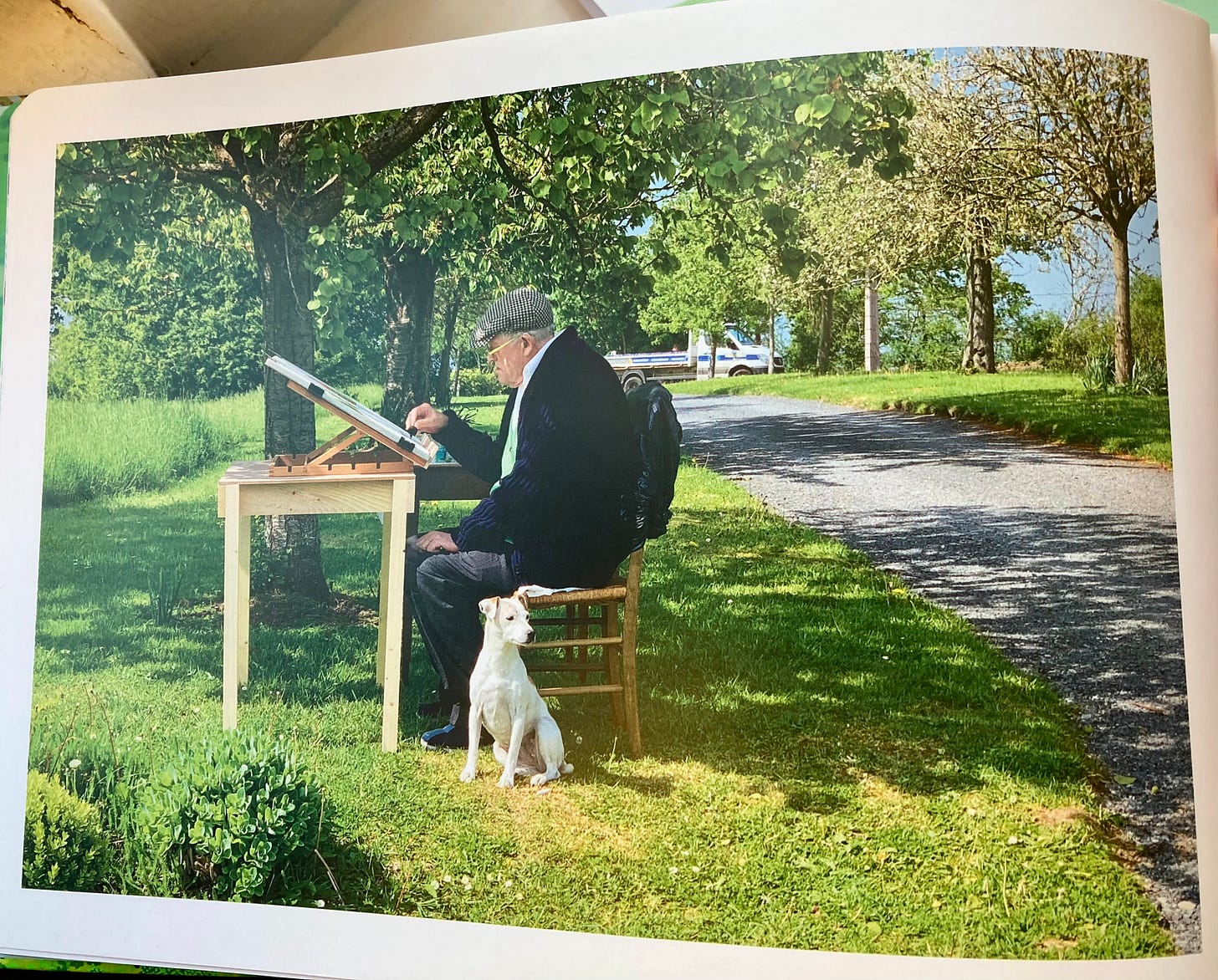

David Hockney, of course, has a huge gaff in Normandy, a beautiful ancient house in extensive grounds which he bought specifically so he could go there and paint ‘without having to drive to his subject’. It’s as if he saw the lockdown coming. He spent that spring sitting in a chair, like me, only he was in his grounds, looking, as only Hockney can look, and painting the arrival and progress of that magical spring on an iPad. With his little dog Ruby beside him.

Now, I love David Hockney. He is like a child, by which I mean he’s singleminded, he takes his work seriously for its own sake, and he cares about the thing he’s making and that’s that. He cares about people making things. I’ve always loved him. He’s so angry that no one is taught to draw now. He was so angry about the closures of small post offices. He went to a formal reception earlier this year at Buckingham Palace to meet King Charles wearing daffodil-yellow Crocs with sky-blue socks, his baggy brown-checked suit, and a bright yellow tie. And made everyone else look wrong. That cheered me up no end.

Anyway, it turns out that that daffodil picture was made on the day after I got sick: the first day I woke up with it, and really knew how sick I was (though of course at that point I thought I’d be better in a week or two, that’s how innocent we all were; that was my hope that spring, that I’d be better soon).

And it turns out that the picture on the cover of the book was made on my birthday.

The book itself is perfect: it’s the size of an iPad, it has rounded corners like an iPad, and the cover folds out and away from the pages like an iPad’s flip cover. The colours are bright and luminous. It is Spring in book form.

Hockney’s ceaseless have-a-go experimentalism, his openness to having a go with the new technology, his springiness, is really energising I think. The opposite of all those older people going on about not being able to cope with computers, or sneering at ‘young people looking at their phones’ on the bus or whatever. You don’t know what they’re doing on their phones, guys. They might be reading Catullus. So he’s got this dot technique for things like blossoms and pebbles, and of course they also imitate pixels. There are squiggles and lines where in a painting you’d expect more ‘realism’ or ‘painterliness’. But Hockney has developed loads of strategies for creating all the textures and elements of his surroundings, and he himself calls this painting. ‘They are’, he says in the interview at the front of the book. ‘I think like a painter on the iPad now. You get one colour and you think no, it should be a tiny bit darker or a tiny bit more bright, and then you do it. Well, that’s like painting’. These squiggles and lines are true to the medium; that’s the ultimate justification for them. Every force evolves a form. The colours are fresh and bold and exuberant, and at times (say, the blossoms, or the new leaves) a surprise of delicacy. A delight of delicacy. ‘That’s what I’m doing all the time’, he says. ‘Getting greens’.

Hockney started doing what he then called drawings on an iPad in 2010, when they came out. He saw the potential straight away. ‘All you need to do on an iPad is make marks, and the first thing I did was to draw with every brush, trying to find all the marks they’d make. Well, there’s thousands actually…’

The foreword to the book is by William Boyd, who knows Hockney, and he writes, ‘If I recall correctly, he had started to do these drawings because, as he explained, the ‘software could finally follow the hand’.

Hockney has always been about the hand.

Now, he says, he’s really painting: ‘I’m using layers a lot more’. And he’s using ‘new, little brushes that I got them to make for me’. You can see this in the images, and the techniques he has developed are pretty fabulous. Impressionism, pointillism, fogginess, wateriness, some beautiful line drawing, some Japanese-looking, some like colour overlay printing. Some like Ravilious. Some like Lichtenstein. They’re digital but they’re, paradoxically, fantastically full of texture. The joy comes off them in great sheets.

The Guardian, among others, absolutely trashed this exhibition on the grounds of being ‘pixelated’ and sloppy and ugly and having been made on an iPad; you can just imagine this sort of reviewer (& I don’t mean anyone personally, because I’m just paraphrasing) being on Facebook tutting at Gen Z, lamenting about modern slang, mocking Millennials, sardonically telling people to say ‘whom’.

No, wait, I will quote it, because it’s interesting. Laura Cumming in the Guardian:

A graze of parallel lines stands for a leaf or cloud; dots of different density are used for seeds, flowers or rising suns; grass comes ribbed, knitted or in sharp little toothpicks. Ready-made motifs proliferate. Blossoms are arrays of danish pastry whorls, both ugly and unpersuasive. Even the innately beautiful structure of a tree is undermined by the stick-figure lines, which lack all eloquence or fluidity. The register is as false and fudged as an electronic signature.

The status of these works is a puzzle. Hockney calls them paintings, although they are in fact iPad sketches in 1.5 metre paper printouts. They cannot marry colour or line, like paint; and they do not have the direct touch of drawings. If you go in too close, you can see hideous distortions, blips and accidental blurs where the technology has failed. Everything lies separate and exposed on the surface.

Up until the ‘innately beautiful structure of a tree’ being ‘undermined’ I was right with her, but I dispute that those lines lack eloquence or fluidity, especially all of it. I don’t find the register in any way false, or the distortions ‘hideous’. She complains because the medium doesn’t behave the same way as paint; she misses the point entirely.It’s like people who only like paintings if they ‘look just like real life’.

This reminds me of an anecdote about Picasso. A workman asks him why his paintings didn’t look like people look in real life. Picasso asks the workman if he has a photograph of his wife. ‘Of course’, he says, takes his wallet out, and hands Picasso the photograph. Picasso peers at it closely for a few seconds. ‘Hmm’, he says. ‘She’s very small, isn’t she?’

If it were just like paint, why would he even bother? I didn’t see the exhibition, where the pictures were displayed as 1.5m printouts, but that sounds fascinating; it would be like being a small animal sitting next to an iPad. A little quick-save at the end of the review, where she suddenly about-faces to say ‘this moving ode to joy’, is what feels false to me.

A great artist creates the taste by which the work will be appreciated, or words to that effect, said somebody or other. A great artist looks at a new doodad and sees a whole world of potential that the rest of us can’t even imagine, because we don’t know the feeling of looking at something and making something completely new appear.

Hockney, more than any artist now living, fills me with inspiration for the love of creation itself, making things, making them new, just the joy of it. And looking. The faith in experiment, the faith in your own eye and hand. The need to acknowledge your need to sit and work. I was raised by people like this. Indeed, my Uncle Mike, one of my four artist uncles (all now gone), framed Hockney’s photo montages in the 80s. So it feels like a reminder of something I need from somewhere both close by and far away. (I’m also reading the other book that commemorates that year, an extended interview exchange with his old friend Martin Gayford called Spring Cannot Be Cancelled. That’s an ebook and it’s nice to be reading it on an iPad.)

Hockney is very lucky, of course; he has money galore, and assistants, and can do whatever he wants to do, even in his old age. His mind is untrammelled by the kinds of worry (not to say panic or terror) that are assailing so many of the rest of us in our little Cost of Living Crisis. And he hasn’t got Long Covid. But maybe that’s the reason why he’s able to keep it so pure. As I’m forever saying to my students and indeed to anyone else, ‘It’s about the work’. The corruption of this is definitely one of the things that are getting in my way. Most of us work better when we’re reasonably happy.

His work is play. (And as Bruno Bettelheim told us — and all children know — all serious play is work. The two are indistinguishable.)

Right now I’m trying to get over the new Covid that I came down with six and a half weeks ago — my fourth bout with the villainous virus. This new one felt a lot more like the first, 2020, one than last year’s Omicron did, and true to that form I’ve already had one relapse when I was beginning to get better. I’m feeling very hopeless at the moment. When I saw the picture made on my birthday (not the cover one; there’s another) it overwhelmed me, and stayed with me, and that’s why I’ve bought the book. My birthday’s not for a couple of weeks but it would never be wrong for me to buy this book.