Pushkin Reciting His Poem Before Old Derzhavin, by Ilya Efimovich Efimovich Repin, 1911

Aaand, the big weekend is nearly upon us! That weekend in the year when all is given over (at least in my little corner) to poetry. 2,000 people will pile into the Queen Elizabeth Hall on Sunday to hear ten poets read their work for eight minutes each. Ian McMillan will be polishing his quips. Bookies will be taking last-minute bets on the prize. Ten poets will be downing the antacids and taking sleeping pills…

Every year since January 2011 or 2012, I’ve given an intensive workshop on all ten books that make up the shortlist for the TS Eliot Prize, the UK’s top-prestige award for poetry. It all gets in a terrible tangle with Christmas, but my early January is a blizzard of books and words and notes and admin and thoughts, and charts, all relating to these ten books. I run the workshop entirely independently, for no reason except that it’s something I do. It started out as a wheeze — just a fun idea a friend had in a pub one night — and then somehow, like the right kind of snow, it stuck.

Every year some of the same people come back, even now that the workshop is split over two mornings on Zoom, with no trip to the pub afterwards. It’s still fun, and it still leads to the online equivalent of people shouting and grabbing a book off the pile to wave around.

But a workshop based on a prize shortlist is not an untroublesome concept. The poetry world in the UK is pretty big, but it’s small. Like Cyril Connolly said, it’s a bunch of hyenas fighting over a dried-up watering hole. There isn't enough water for every poet to feel fully hydrated, if you’re relying on poetry to supply all your hydration, and this is the underlying cause of much sourness.

Simply put, it’s much harder to build a lucrative poetry career — that is, to earn any money in poetry — if you’ve never won one of the big prizes. Or even, sometimes, just to get your work published at all. This is why the beat poet Michael Horovitz always talked about ‘the Enter Prize Culture’, and I love him for it.

The thing is, our watering hole is full of holes. There aren’t that many prizes for poetry in Britain. We’re prize-poor. And increasingly there seems to be a trend that American poets also published in the UK are likely to win our prizes; their books are terrific. But very, very few UK poets are eligible for American prizes, because America is vast, and has so many poets of its own, and the dominant poetics is (one for another day) different from the UK. You pretty much have to be published by Faber to get a deal in the US. So the traffic is mostly one-way.

But like it or not, we all, all us poets, need the poetry prizes, whether we’re winning them or not. They are the garden hose. They put poetry in the sun for its little moments, its short growing seasons in a cold climate, and at least a few people who don’t normally read poetry will notice a name or two, and some books will sell, and keep some of the presses watered, anyway.

The Forward Prize — like the Poetry Book Society, the book club TS Eliot set up in the 1960s — has the most explicit remit to bring poetry to people who might not ordinarily read it. It’s actually the Forward Prizes, plural, because they run one for Best Collection, one for Best First Collection, and one for Best Poem published in a magazine, so that spreads the glory a bit.

We all know, by the way — everyone in poetry actually knows — that there’s no such thing as ‘Best’. We know that poets are different. Prizes are important to poets, sure — and the Eliot in particular offers a whacking £25,000 first prize to the lucky one — but the idea of prizes is not just for poets; it’s for encouraging non-poets to feel safe to wade into the water and read some poetry. In fact, the TS Eliot Prize was started as an adjunct to the Poetry Book Society, whose four seasonal Choices were automatically shortlisted for the big one. The two only split apart a couple of years ago. I’ve had friends on the verge of tears after not being chosen by the Poetry Book Society panel for its seasonal Choice, or a Recommendation.

There are other prizes, and they also further careers. The Poetry Society, a membership organisation made up mainly of poets, runs (among other activities) the annual National Poetry Competition, the Foyle Young Poets Competition, and the Popescu Prize for translation, also has this same remit, and it tends to promote, commission, etc, those poets who’ve won those awards. The Society of Authors administers the Somerset Maugham Award, and I think one or two others that poets can qualify for: also prestigious. Even at the shallow end of the prize pool, publication is helped along by winning an Eric Gregory Award for poets under 30, or being a Foyle Young Poet.

And we know that work, art, thrives in the sunlight of recognition and praise. So who to praise? And doesn’t praising one poet in public automatically entail not praising everyone you didn’t happen to mention?

Needless to say, there are all kinds of ways to run a productive and even widely appreciated artistic life without winning prizes. This is why we love to list the great writers who never got a Nobel. Michael Horovitz lived in a sunshine of his own making, away from the Enter Prize culture, and he was still holding Poetry Olympics events and gigging well into his eighties, until the pandemic struck. We write and share our poems, we get published, and we review books in magazines, and if we’re lucky others review ours. There is recognition without winning prizes. Just not the recognition of institutions, and it's this that will get us noticed beyond the poetry puddle. Radio!

And there are an awful lot of books — wonderful books — that don’t make it onto this one shortlist chosen by three judges. I’m just here to talk about the ones that did, treating them as a synecdoche, viewing them as a ‘where we’re at’ snapshot. (This is the same principle that underlies my weekly Poem Talk sessions, too — on a Thursday lunchtime — where we literally talk about one poem for 45 minutes to an hour. It’s an extraordinarily rich way to experience a poem.) For me, much of the joy of poetry comes from how huge it is, how capacious, an endless sea with many shores in all kinds of climates. The English language is a multifariously and prodigiously expressive instrument. I like to help even seasoned poetry readers to discover something from a different shoreline from their usual destination.

Every year I joke that I’ll run a workshop on ten books that didn’t make the Eliot shortlist — but the minute you think that, you’re thinking about how to choose them — are they the ten that should have been on the TS Eliot list? How do you decide that? Are they ten you think would never have been chosen? And why wouldn’t they? In short, it’s just another shortlist — only this time it’s the KEB Prize shortlist, and you feel bad about every brilliant book that didn’t make it onto that.

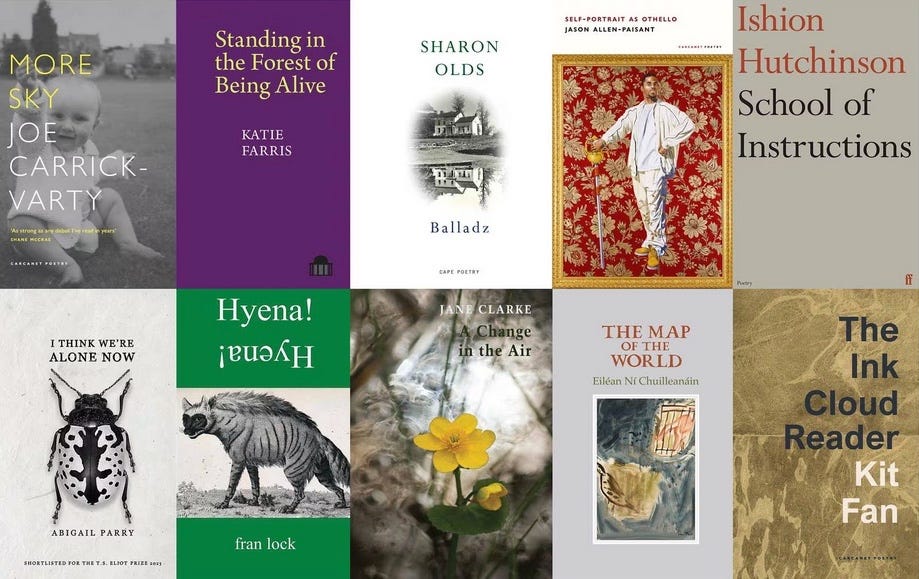

So what about this year’s TS Eliot shortlist? Here they are:

These ten books I’ve taken precious time out from to write this today: what’s so great about them? Here’s what Paul Muldoon, the doughty Chair of Judges, said:

“We are confident that all ten shortlisted titles not only meet the high standards they set themselves but speak most effectively to, and of, their moment. If there's a single word for that moment it is surely 'disrupted', and all these poets properly reflect that disruption.”

There's a conversation (another one for another day) to be had about when and why the shortlists started changing, but the light has definitely been shifting for the past 15 years, and there was a sudden moment in about 2015 when all of a sudden the shortlists became actually multicultural. It isn’t just about identity politics, it’s about how people play the instrument of our shared language, it’s about words and sounds and outlooks and what we can make a poem do; what we want to make a poem do. It’s about not just the ambition of the poet — and this year’s shortlisted poets are very ambitious indeed — it’s about our own ambition as readers, and for the poetry we want to be able to read.

The list this year, or rather the pile of books, is a different kind of multi, though it also contains books by two Black poets, and two by queer poets. There are not one but two older women with long grey hair. That's optics, okay, but given the flack Mary Beard gets, I think it's something. It contains a thing I haven’t noticed much in other years, and that's class. Actual class politics.

It also contains two books that are unashamedly difficult, complex, dense, that need working at — one with many Biblical references — and a third that contains lines in three or four languages or idioms, and a highly structured theme based on Othello. And one of the linguistically dense ones is published by a tiny press in Ireland. (It’s notoriously hard for small presses to gain this kind of exposure, if for no other reason than the expense of suddenly operating on this scale. The Little Engine That Could is cheering me enormously!) There is a lot more information on the TS Eliot Foundation website about all these books, and also previous years’ shortlists.

There are two first collections on the pile. Not so long ago the Eliot was considered a prize only for eminent, distinguished poets, not newly fledged ones. There was a lecture delivered by the winner every year, for one thing. I liked that, and I miss those lectures. They were idiosyncratic and always interesting. But I’m not sorry the prize is reaching out more deeply into the poetry world. And these days, many first collections are by poets who’ve been well known on the scene for a decade or more. Two or more pamphlets might have got almost as much attention as the full, when it arrives, collection. I was stunned to discover that Paul Stephenson’s Hard Drive (Carcanet) was his first collection, I’ve been a fan of his work for so long. Ditto, in 2020, Joe Dunthorne’s O Positive (Faber). I’m sure anyone on this year’s shortlist would be more than capable of delivering a whopper of a lecture, just as either Dunthorne or Stephenson could.

So in a deeply flawed system, in a deeply flawed world that has ever been thus, &c, &c, I am more than happy to pick up this snapshot and deliver it to a Zoom-room full of people who will then be better empowered to appreciate the readings on Sunday night — to cheer and celebrate when one poet is lifted onto the shoulders of the rest of us for a bit — and indeed, to buy the book or two they’ll really love. And the maybe to go and seek out another.

There’s still room to join if you fancy it. It’s 10am-1.30pm Saturday and Sunday mornings 13/14th, it’s £65 for the two mornings (and there are concessions available), and all the info is on my website. You only have to drop me a line to get on the list.