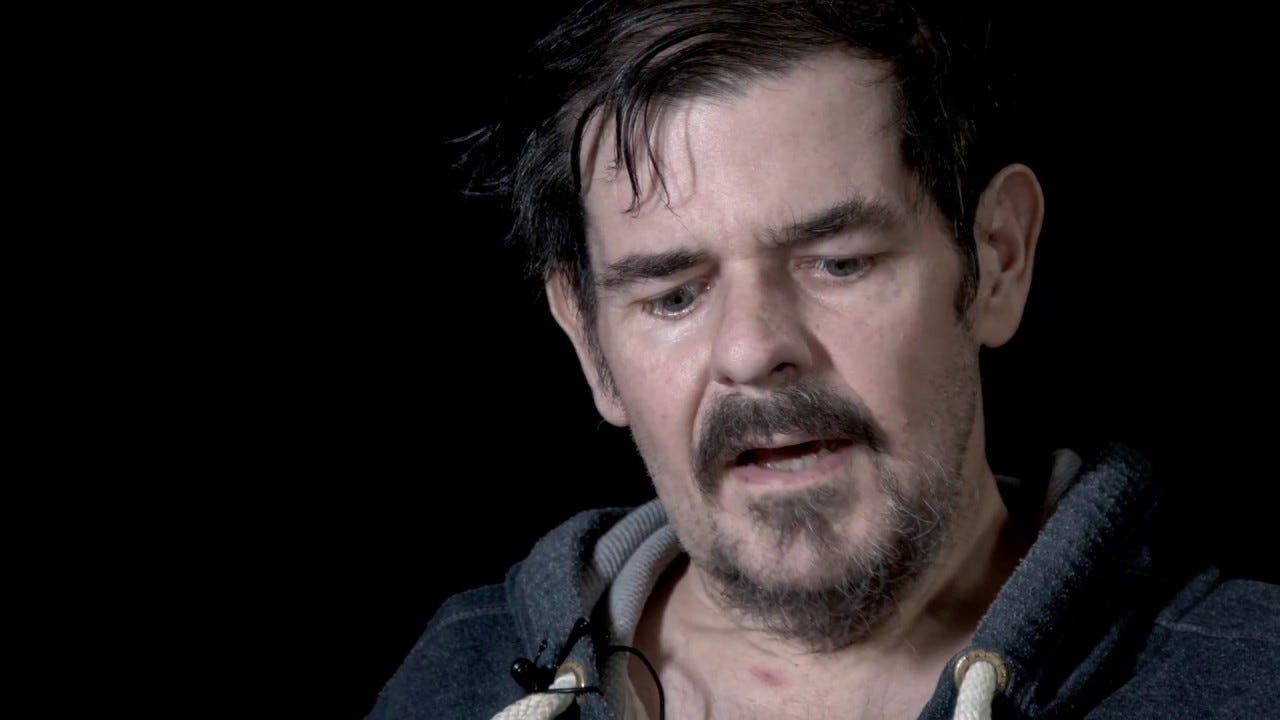

Two years ago the news came: Roddy Lumsden had died. Actually I think the news came on the 11th, and I can’t remember now how I heard; I think maybe someone called me. I can remember pummelling the sofa in rage seconds later, but I don’t remember hearing the news. It wasn’t a surprise, as he’d been ill for years. But a death is always a shock, the death of a colleague and peer — and it happened at the beginning of the biggest weekend in the poetry year: TS Eliot Prize weekend.

In fact, he’d been ill for more years than most people were prepared to recognise. I cross-examined him one night in 2011 when he was looking green and said he’d ‘had a stomach bug’. And then there was the business of that ‘weird concussion’. One night in the pub after an event in about 2013 or 2014 he called me over: ‘Let me ask you a question, and I’ll do what you say’. Okayyy… ‘I still have this weird concussion [it had been months]. Should I go to the doctor?’

YES, I said. ‘Go to the doctor!’

‘Okay, I will’, he said.

‘Why will you go if I say so?’, I asked him.

‘Because you’re a mum’.

Of course he never went. And I now know that if someone is looking a bit green, it means only one thing: liver. The only other person I’ve ever seen look that colour was already on the transplant list, and spent a week in hospital after we rushed him there.

The night Roddy’s condition became really unavoidable was the night in 2016 when Sarah Howe won the TS Eliot. (That after-party was a very serious affair.) His own last book, So Glad I’m Me — for my money his best in years — was shortlisted, but (shockingly? Strangely? Fairly?) it didn’t win. Who knows the minds of judges. By then he was in a nursing home in South London, and he kind of gave up after that.

And in 2020 Ian McMillan remembered him from the stage of the Royal Festival Hall at the reading on the 12th. People were subdued, pale, a few tearful at the awards ceremony on the 13th. And here we are, two years nobody then even imagined later, and the date rolls round again. Roddy’s funeral, on 10th February, was the last time our extended poetry family — it is a family — got together, the last big night out, the last piss-up — and it had been a reunion. In the event, how could we know, it was the last time most of us have seen each other, and now people are scattered to the winds. (There were a few people missing that day, unable to travel because of a huge storm that had been battering the country for two days; one of those was Roddy’s oldest childhood friend, and another was his publisher, Neil Astley of Bloodaxe Books. Ahead of the ‘absence’ curve.)

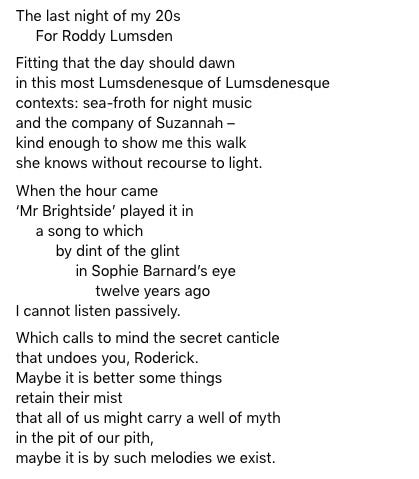

I don’t even remember the TS Eliot Prize weekend last year; none of it happened. This year it did: I was persuaded to run my annual workshop on all ten shortlisted books again, only now online. The reading went ahead as usual last night, only many didn’t go. And tonight the awards ceremony will take place. We’ll see what that’s like. This year’s shortlist bears the traces of Roddy, in that his students are now being put up for these big awards; one of this year’s crop, Kayo Chingonyi’s A Blood Condition (Chatto & Windus), contains a poem for Roddy:

There was one thing I meant to do in 2020 before it all got swept away in the first lockdown. I was asked to write an obituary of Roddy for the Telegraph. It was a tight word count, given the breadth of his activities, and all the people I felt had a stake in his legacy, but I did the best I could. When it was published it was heavily cut and thus a little distorted, and I meant to publish my original copy, but then I got sick and that was that. But I have minded that the essay I wrote — it became like a little essay — never saw the light of day. (Looking at it now, there seems so much more to say, too.)

So here it is:

Roddy Lumsden, who has died aged 53, was a Scottish poet, crossword writer, quizmaster, trivia blogger, music enthusiast, editor and teacher who changed the face of contemporary British poetry — and planted a little kiss on the face of contemporary American poetry, too. Since the millennium, through teaching and mentoring (often for free), he influenced hundreds of UK poets, introducing the work of contemporary American poets who excited him, including Chelsey Minnis, Brenda Shaughnessy, DA Powell, Cate Marvin (whom he met as an exchange student in Edinburgh), and Kathleen Ossip, among others.

Many poets he worked with have gone on to be well-known and even more garlanded: TS Eliot Prizewinners Jen Hadfield, Sarah Howe and Hannah Sullivan all flew under his wingspan, however briefly. As the poetry editor at Salt he published Fran Lock, Amy Key and others. Hundreds more have been taught by him, taken part in his reading events, argued endlessly with him on several online forums, or just known him as a face at poetry events. On his topic — the glittering possibilities of the present — he knew seemingly everybody and everything.

His work merged the rhyme-friendliness of UK poetry with American beat and postmodernist trends, developing a distinctive style of his own that was rich and strange in both lexicon and image, primarily musical, and emotional. He was fond of idiolect — each person’s personal, distinctive language — defining his as ‘the unusual words not recognised by a spellcheck’, and said, ‘I like idiolects — they always give an odd flash of the atmosphere’. For each book as it came out, he would publish the long list of words, featuring the undictionaried modern (tangas, indie, gonk), and the archaic and downright dreamy (skittled, thrip, butterless, eidolon, goluptious, teaselled, goaty, and fluthered).

He invented complicated poetic forms — the Akhmatova-based sevenling and the hebdomad both stipulated content structure along with form, and there were others. He ran themed readings, in which he would invite dozens of poets to write and perform one poem on a given theme — a US state, or line of Bob Dylan which he’d assign. These, like his forms, reached well beyond his classes. Open any book by a UK poet and you’re bound to find one.

Roddy was a gossip, a provocateur, an impresario to his bones. He was prickly, set in his views, and also vulnerable, somehow ethereal; he literally lived for poetry, and beer. He was obsessed with youth, and on his 45th birthday confided to me that he had no model or image of himself past that age. Brenda Shaughnessy describes him as ‘a singular, oddly magical person’. His final illness, with cirrhosis, was four years long and very distressing. The US poet Robert Archambeau said last week, ‘I still remember Roddy in a bar under the El tracks in Chicago, leaning over his glass and reciting his lines: ‘So I will wear a crown of crowns/and promenade the borderlands and bounds/of my domains…’

Roderick Chalmers Lumsden was born in St Andrews on 28 May 1966, youngest of three brothers, to Hamish Lumsden, an electrician, and Betty (also née) Lumsden, who worked at the university. He attended Madras College in St Andrews, and then the University of Edinburgh.

After graduating, alongside fellow poet AB Jackson, he famously scratched out a living by playing the trivia machines in pubs, and also wrote word puzzles for The Scotsman, ‘until sudoku came in and I got the heave’. (His crossword career did not end there; he had several crossword-writer names, at different papers.)

In 1991 he won a prestigious Eric Gregory award for poets under 30, and Bloodaxe published his first book, Yeah Yeah Yeah, in 1997. The following year he moved to London to begin his career in earnest. The late 90s was a golden time in London poetry, and Kathryn Gray, his first protegée (published in the Anvil New Poets 3 anthology, co-edited with Hamish Ironside in 2004) remembers: ‘It seems as if I spent all my time the year 2000 in the company of Michael Donaghy, Roddy Lumsden, John Stammers, and Andrew Neilson. Michael was the beautiful magus of all the mysteries; John was on the brink of so much success and had scintillating swagger and wit; Andrew was the brilliant emerging poet and already remarkable critic. And then there was Roddy… Nothing that has happened to me in writing would have happened without Roddy’s hand.’

Indeed it was because of Roddy that I began reviewing for Poetry London, and that I taught at the Poetry School.

His long-running BroadCast reading series began as a fundraiser for Donaghy’s widow and child, and then became a fixture; many, many poems were written as a result of his themed readings where he would ask everyone to write a poem on an assigned theme.

He also taught at the Poetry School and independently, and his students formed tight-knit bands. He launched, and ran until he was too ill, an annual reading in London for each year’s crop of Gregory winners — a public recognition that was also many poets’ first real exposure in the capital.

After Donaghy’s death in 2004, Roddy took over his famous ‘Wednesday group’ at City University. He edited a pamphlet series for Tall Lighthouse, and several anthologies for Salt, as well as the ‘generational’ Identity Parade for Bloodaxe (2010).

As poetry editor at Salt Publishing he published Fran Lock, Mark Waldron, Amy Key, Nia Davies, David Briggs, Rebecca Tamas, and others. When he was dying, Amy Key organised a list, called ‘Thank You Roddy Lumsden’. Over eighty poets wrote to thank him.

Yeah Yeah Yeah was shortlisted for Forward and Saltire prizes. The Book of Love (2000) was a Poetry Book Society Choice, and shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize. Mischief Night: New & Selected Poems was a PBS Recommendation. His final collection in 2017, So Glad I'm Me, was shortlisted for the T.S. Eliot Prize and the Saltire Society Scottish Poetry Book of the Year Award.

Roddy Lumsden, born 28 May 1966, died 10 January 2020