Dear readers, whoever’s stuck with me this far,

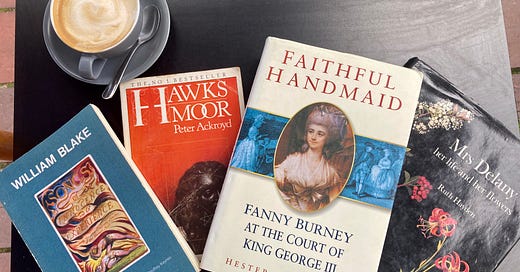

Thank you! I have a list as long as my arm of the things I was supposed to be writing in this space this year. I haven’t done it. Books, pictures, movies, political observations. I still intend to write some of them, though maybe not so much the political observations which feel so much less trenchant now that we’re just in a horror show. Above is just a taste of a little trip to the 18th century I found in the local secondhand bookshop this past weekend.

My little bio says (or used to say anyway) that I’m writing this blog from the front line of the precariat — a term now rendered so redundant by the events of the past three years alone that it seems merely quaint: a reminder of a time so sweet that we imagined someone might not be precariously paid, housed, fed.

In the book I still need to finish, about my year of upheaval and sofa-surfing, I say my life has, Gumplike, been there for the key events of my lifetime, at least as relates to the growth of the housing crisis and precarity. I’m still, true to form, living the Zeitgeist — but now it’s also the Long Covid one, the lockdown & aftermath one, and the ‘OMG I’ve been diagnosed with ADHD’ one. This last is the one I least want to write about, as everyone is at it, but it’s the one I’ve been plunged into most deeply in recent months, as I finally take stock of all the ways in which it’s shaped my life. It has kind of shut me up in the meantime — doing all the research and finding out what has been actually happening my whole life —the poor choices, impulsivity, lack of a concept of time, doomed perfectionism, inability to tolerate boredom, the motor driving me that’s accounted for so much over the years, the lack of a degree which would have at least rendered me employable, and the answers to a thousand other questions.

Yeah, I know: trendy diagnosis label, et voilá: ‘Everyone has a bit of ADHD, don’t they’.

My answer to that is not polite, but I will point out that if you’d like to be as flaky, forgetful, self-doubting, often immobilised for no reason anyone can think of, and frequently kind of lost as I am, you’re welcome to it.

I’m one of the lucky ones, I know. I have a superpower: I can write. Sort of. I do feel it, and I know it’s not down to anything I did — I had a photographic memory for spelling when I was six, I never had to try, I absorb information really quickly (losing some details along the way, of course, they fly off like pebbles under the wheels of my super-fast brain) and when I finally get down to it an hour before the due date, I can (sometimes) work really fast. But it’s not the same as having got a degree, or being able to just buckle down, or not having to always work on not appearing weird.

Tom Hanks has ADHD, you know. You can see it, can’t you? Though of course he’s not having to sit there asking himself how the fuck he ended up living by himself in a tiny flat fifty miles from home, claiming benefits. (People with ADHD are statistically much more likely than the general population to experience homelessness, joblessness, broken relationships, precarity, and poor health outcomes.)

I almost don’t want to write about precarity any more, to be honest. It’s depressing, and it’s so mainstream now. It’s everywhere you look, in every corner of the news. It’s not just rents going up exponentially, it’s homeowners’ mortgages (a friend reckons hers could easily double when her current deal expires next year), which means it’s also buy-to-let mortgages, which means it’s also rents… Actually many buy-to-let owners are now talking about giving it up, so there will be even fewer properties available for people like me, which will — you know — drive rents up. And of course the housing component of Universal Credit — which has deliberately been set below the actual cost of a flat — hasn’t been updated since 2019.

With all this, homelessness is rising even faster now than at any time in the 12 years since Cameron and Osborne came in. It stopped during the lockdown when the government managed to do what it’s always said it couldn’t do, and now says it can’t do again, which is get everyone in out of the cold — and ban evictions (though many people did lose their homes during that time) — but since then homelessness has gone up like a rocket. Even among people who are in work. And for anyone who doesn’t have a place to live, a place to live is now further away than it ever has been.

My cousin Stephanie in New York is currently living in her van.

I was a little stunned recently to learn that something like 36 per cent of UK households are homes owned outright. I know this reflects the tipping of the population towards older people who were able to buy their homes much more cheaply decades ago, and have thus been able to pay off their mortgages, but a third of all of us! It surprised me. Moving forward, a room of someone else’s seems to me like where more and more of us will be living, which proves the utter, absolute lie of Margaret Thatcher’s project — and takes us back to how things have always been, really.

Out of the four books above, it strikes me that three of them are either by or about people who experienced, various forms of homelessness. (And as Peter Ackroyd’s Nicholas Dyer makes a point of telling us over and over from his vantage point of 1713, we live as much in time as in place; through (or via) time, not all of it ours, as we do in place, which can only be ours while we’re we’re standing on it.)

There are other books I want to write about — not least my own forthcoming poetry collection, Joe Hill Makes His Way into the Castle, ‘poems of justified rage delivered with skill and lightness’, with the iconic small press CB Editions. I’ll be back soon.